In recent years, I started to notice a common thread running through several major cultural flashpoints: homosexuality, transgenderism, AI, and Covid. At first glance, these topics seem disconnected. But the more I examined them, the more I saw a hidden connection—a way of thinking that undergirds them all. That underlying theme is an ancient Christian heresy: Gnosticism.

What Is Gnosticism?

Gnosticism teaches that salvation comes through secret knowledge (gnosis) and that the physical world is flawed or even evil. In this view, the true self is immaterial, and our bodies are little more than prisons. Early Christians rejected this heresy forcefully. The Apostle John, for instance, insisted that anyone who denies Jesus came in the flesh is not of God (2 John 7).1For many deceivers have gone out into the world, those who do not confess the coming of Jesus Christ in the flesh. Such a one is the deceiver and the antichrist.

Today, Gnosticism hasn’t disappeared. It’s just morphed into new forms.

Gnosticism and the Sexual Revolution

Take homosexuality and transgenderism. The underlying belief here is that our bodies don’t matter—or at least, they shouldn’t have the final say in who we are. If someone’s desires conflict with their biology, then biology must yield. In transgenderism especially, the body is treated not just as irrelevant but as an obstacle to overcome. It’s a mindset that says, “What I feel on the inside is who I truly am—my body just hasn’t caught up yet.”

This isn’t a scientific outlook. Ironically, it clashes with Darwinian evolution, which says our physical traits exist for a reason. Our anatomy speaks to our purpose. Even noted biologist-atheist Richard Dawkins has made similar observations, emphasizing that male and female bodies evolved for reproduction, and that denying the biological basis of sex is anti-scientific. He certainly doesn’t frame this as a critique of Gnosticism—but the resonance is striking.

Gnostic thinking rejects the biological basis entirely. It tells us that truth is found in the internal self, not the external form.

Virtual Reality, AI, and the Disembodied Future

This disembodied way of thinking also shows up in technology. Virtual reality is now marketed not just as entertainment but as an alternative to real life. Marc Andreessen, one of Silicon Valley’s top voices, once argued that those who value the physical world are simply enjoying their “reality privilege.” For most people, he claims, the digital world offers more meaning, more justice, and more joy. In a widely shared 2021 interview, Andreessen framed virtuality as a more equitable frontier than physical reality, arguing that investing in digital life is not only desirable but ethically necessary for those lacking “reality privilege.”

Mary Harrington, a feminist critic of transhumanism, connects this to the rise in trans identities. Kids who grow up immersed in virtual spaces—from Minecraft to Instagram—come to believe that the body is endlessly editable. If you can modify your online avatar, why not your real one?

She labels this phenomenon “Meat Lego Gnosticism”, vividly depicting a mindset where our bodies are deconstructed and reassembled, like LEGO blocks, at our own discretion rather than respected as integral, given wholes.

Artificial intelligence takes this logic even further. Some experts now openly ask whether unplugging an AI that claims to be conscious would be morally equivalent to killing a human. Why? Because if humans are just biological computers, then a silicon-based computer might be a person, too. Once again, embodiment is dismissed as unnecessary—or even oppressive.

Christianity Is Embodied

The problem is that this is profoundly anti-Christian. From Genesis to Revelation, the Bible insists on the goodness of the body. Creation was called “very good.” Adam and Eve were given bodies with sexual differentiation and purpose. The Law regulated food, clothing, and ritual purity—bodily matters. Circumcision, anointing, sacrifices, baptisms—these are not incidental to the faith. They are expressions of it.

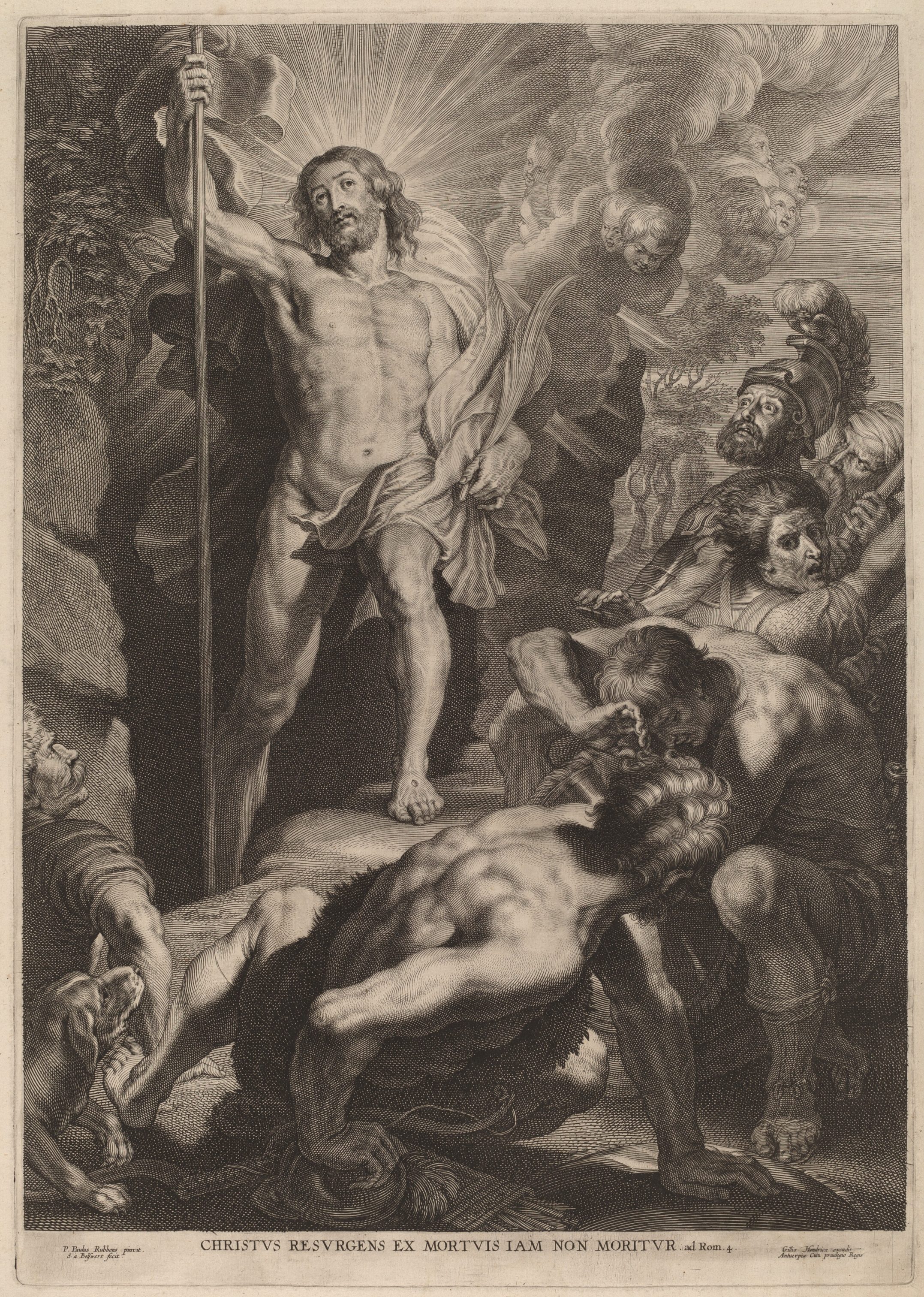

And then came the Incarnation. After creating bodies, and calling them good, God took on a body. He didn’t just give us ideas or a philosophy—He lived, suffered, bled, and died. He rose again with a body, and He gave us bodily sacraments: bread and wine, water and oil.

Christianity is not a disembodied information exchange. It is a flesh-and-blood, incarnational way of life. When we start treating livestreams as a sufficient replacement for church, or when we reduce Christian teaching to mere data transfer, we’re slipping into a Gnostic mindset.

Many in the tech world find the very idea that our nature has been given to us—rather than designed by us—to be a kind of offense. Yuval Harari, for example, boldly declares, “Organisms are algorithms,” and envisions a future where human life is no longer shaped by divine design but by human reengineering: “Science is replacing evolution by natural selection with evolution by intelligent design—not the intelligent design of some God above the clouds, but our intelligent design.”

For the modern mind, it’s galling to be told that our identity, limits, and even our flesh have been handed to us. The Christian worldview says we are fearfully and wonderfully made; the new Gnosticism says we are merely constructed—and ought to be reconstructed at will.

Why It Matters Now

Covid accelerated this shift. We were suddenly told that human bodies were dangerous. The ideal became disembodied—stay home, go virtual, avoid touch. What shocked me most was how quickly many Christians accepted this. The body, once central to Christian worship and community, became an afterthought.

But this wasn’t a new temptation. Gnosticism has always haunted the Church. What’s new is how persuasive it’s become in the age of digital technology and identity politics.

When Christians start believing that the body is incidental to the faith—or to being human—we’re not just making a theological mistake. We’re surrendering to the spirit of the age. We’re forgetting that Jesus rose with a body, that the Church is a Body, and that salvation is not just for our souls but for our whole selves.

Embodied Discipleship

What does it mean, then, to resist the Gnostic pull? It means leaning into our createdness. It means honoring our bodies as gifts. It means worshipping in person when we can, serving one another physically, and refusing to reduce faith to a collection of doctrines floating in the cloud.

To be Christian is to be human in the fullest sense—mind, soul, and body. Our world doesn’t need more clever ideas. It needs the witness of embodied lives: people who live out truth in their flesh and bones, who love with their hands and feet, and who follow a Savior who did the same.

Gnosticism says salvation is found in escaping the body. The Gospel says it’s found in the Word made flesh.

And that makes all the difference.

+++